NEW YORK — Sometime in the 1790s, George Washington journeyed by horse-drawn carriage from Philadelphia to lower Manhattan. It would’ve been a miserable three-day trek over 100 miles of dirt and rock, but not as dreadful as what awaited him at the end of the road.

There, at a home on William Street, the roughly 60-year-old president would have sat before a sunlit window, opened his mouth wide, and had his last remaining tooth twisted out by a dentist who later turned it into a trinket.

No anesthesia. No comfortable dentist chair. Pliers. A rocking motion, a twist or two. Out.

The tooth survives to this day — the one piece of Washington, aside from hair clippings, that’s still above ground — as does a denture that was crafted with a hole to accommodate the president’s tooth.

Neither that denture, nor any other owned by Washington, was made of wood, as you might have heard. Rather, they were crafted from gold leaf, lead plates, hippopotamus ivory, and the teeth of cows, horses, and, likely, Washington’s slaves, who received a relative pittance for each of the nine teeth he took from them.

While historians have long known that Washington’s teeth aren’t wood, the idea that they may have belonged to his slaves is a modern addition to the historical record, and underscores the nation’s seemingly endless preoccupation with the man’s mouth.

For good reason, perhaps. The still-unfolding story of Washington’s teeth offers a window onto his role in the birth of modern dentistry, how the nascent profession forestalled and concealed the collapse of his oral health, and how his teeth were essentially props of geopolitical theater starring a low-brow, foul-mouthed young country crashing the party of civilized nations.

In a dark, chilly room at the New York Academy of Medicine, Arlene Shaner, the academy’s historical collections librarian, recently donned surgical gloves and unboxed the institution’s crown jewels: a golden pocket watch and a matching chain that bears a wax seal stamp; a pendant bearing George Washington’s face; and a windowed case holding a tooth, root and all.

The case is inscribed in tiny cursive: “In New York 1790 Jn Greenwood made Pres Geo Washington a whole sett of teeth. The enclosed tooth is the last one which grew in his head.”

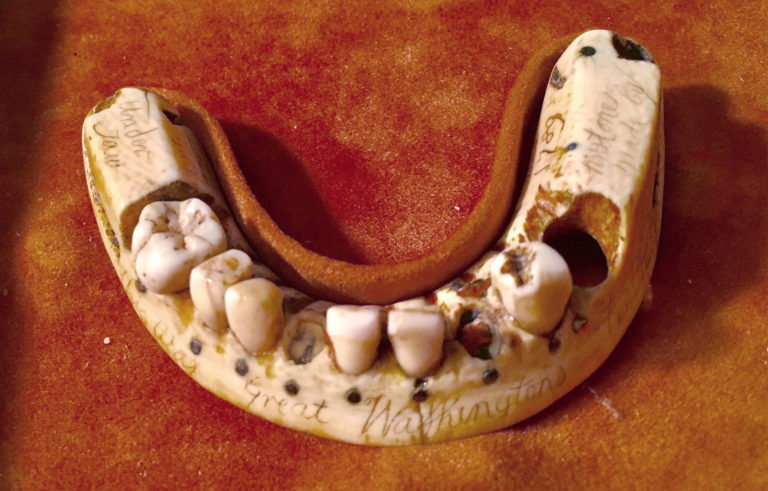

Shaner slipped the cover off another box, revealing a set of lower dentures with another inscription: “Under jaw. This was Great Washington’s teeth by J. Greenwood. First one made by J. Greenwood 1789.”

The denture was one of many Washington owned during this lifetime, and one of several still in existence. It has six discolored and mismatched teeth, two small gaps where teeth evidently broke off, and grooves for the now-missing springs that pressed the dentures to Washington’s gums. An outsized hole on the left side marks the location of his last tooth.

Porcelain dentures wouldn’t appear for another 50 years or so. Like many others of the day, these were made from hippo ivory, which is durable and easy to carve. And like the most expensive dentures of the day, this one was filled with human teeth — maybe those of desperate souls who’d read John Greenwood’s newspaper advertisements offering a .246-ounce gold coin, or a “guinea,” for each healthy tooth.

Or, perhaps, these were the teeth of Washington’s slaves. At least once, in 1784, he bought his slaves’ teeth, paying around 14 shillings each, which was a fraction of what Greenwood paid his donors.

Whether Washington used his slaves’ teeth to shave a few guineas off the price of the Greenwood denture is a mystery, but he still paid dearly: $60 for a set, the equivalent of four month’s wages for the average non-slave, full-time worker in a mid-Atlantic state.

Most others in this still-young nation resigned themselves to hiding their gapped teeth behind tight-lipped smiles. Modern dentistry, after all, had yet to come into its own.

One of the pioneers was Englishman John Baker, who lived for a time in Boston, then moved to the more affluent South, where he eventually served as Washington’s dentist. Before leaving Boston, he taught dentistry to others — most notably, Isaac Greenwood, an ivory turner and mathematical instrument maker.

The younger Greenwood’s big break came in 1789, when he was 29 years old. Congress elected Washington president and called him to New York, the nation’s first capital. Washington needed a new dentist. In a small town of 33,000 people, someone trained in John Baker’s techniques would have had caught the president’s eye.

![]()

Historians can’t trace the genesis of Washington’s wooden-teeth myth, but one possible explanation is that he ate with his fake teeth in his mouth.

Keeping up appearances was critically important, especially for Washington. Tooth loss was associated with gluttony, poor hygiene, bad breath, lack of self-discipline, and worse, syphilis, which often presaged tooth loss because it was treated with mercury.

It’s one thing for the rank-and-file citizenry to carry that stigma. Washington, in effect, risked stigmatizing the entire country.

University of Delaware historian Jennifer Van Horn detailed these and other nuances of Washington’s denture troubles last year in the journal “Early American Studies.” To Europeans, America was already place of gap-toothed folk, and if Washington himself embodied the European stereotype, he would have further opened the new nation to ridicule.

“Simply stated, Washington was the nation,” she wrote.

If the nation was going to be taken seriously on the geopolitical stage, Washington needed to look the part during dinners and speeches. Eating and speaking with dentures, however, was a massive chore, especially if one had no teeth to help keep them secured. Wire springs pressed the dentures to one’s gums, but if a person opened his mouth too far — and if, like Washington, one’s gum loss was extensive — the dentures might fall out.

Most people in such situations, then, spoke little when wearing dentures, and they removed them for meals. Historians famously attribute Washington’s clipped, subdued speaking style to his dentures. As for the dinners he hosted with foreign ambassadors and state leaders, Van Horn suggests that Washington barely ate a bite.

He did drink wine. Lots of it. And the practice earned a private rebuke from his New York dentist, who noted that Washington’s dentures were “very Black Ocationed by your soaking them in port wine, or by your drinking it.”

Civilized people didn’t talk about their teeth in public until long after Washington’s day. The Mount Vernon museum, in fact, wouldn’t deign to display his last-surviving full set of dentures until recent decades, where they quickly became the most popular exhibit.

It’s a mystery, then, how John Greenwood mustered the courage to ask Washington to keep his last tooth, or, indeed, whether he even asked. Such a request may have been easier for someone who knew he was Washington’s favorite dentist, as the president indicated in letters.

He continued working long after, and passed his practice onto his sons, who kept Washington’s dentures, their father’s watch and, of course, the tooth.

The family kept the collection until finally donating it to the New York Academy of Medicine in the 1930s. Also in the collection were Greenwood’s homemade dental tools, and dentistry’s first “dental engine” — aka a foot-powered drill that Greenwood made from a spinning wheel.

The drill itself is gone, but most of the contraption remains in its rickety, skunkworks glory.

Shaner, the NYAM’s rare book librarian, brings out the collection for younger visitors and others for whom she wants to enliven history.

She actually has access to a second presidential mouth, courtesy of Grover Cleveland, who had secret surgery to remove a tumor, five teeth, and a chunk of his upper jaw in 1893.

He had anesthesia, and the NYAM has a mold of his reconstructed maw.

“Every now and then we bring it out,” she said. “He doesn’t seem to get the same reaction as Washington.”

Exciting news! STAT has moved its comment section to our subscriber-only app, STAT+ Connect. Subscribe to STAT+ today to join the conversation or join us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Threads. Let's stay connected!

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.